Why Gravitational Radiation Starts at the Quadrupole

“Out of intense complexities, intense simplicities emerge”

— Winston Churchill

I have always been absolutely awestruck by the fact that gravitational radiation can only be quadrupolar and never understood it quite intuitively until I took some time and found analogies and visualizations to understand it. I am documenting this for future reference for me and anyone who would find this useful. So let's begin!

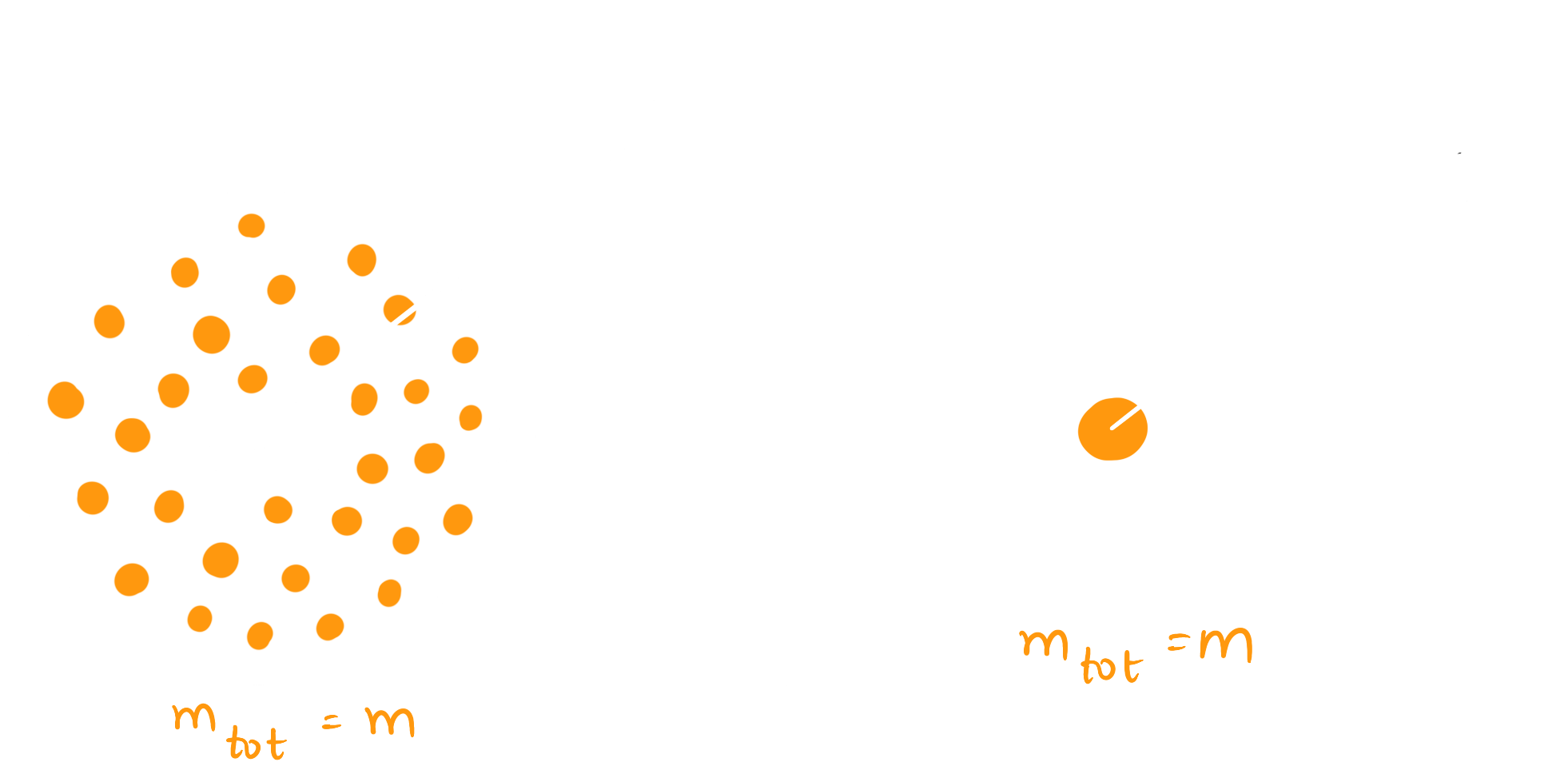

Figure 1: Newtonian shell argument and equivalent point mass

For understanding something that I do not have a grasp on at all, I generally start from what I do understand about the topic. Naively, if I were to ask my undergraduate self: "How can you possibly produce gravitational radiation?" I would have had some ideas. Let me start from there.

Mass produces curvature and this curvature is what forms our notion of gravity. So if I were to provide some momentum to this mass and change its distribution spatially, the metric which helps us define curvature should change and that should produce gravitational radiation. This idea isn't entirely wrong but to understand the beautiful nuances of general relativity, we need to dive in deeper.

Consider a uniform spherical mass distribution of mass $m$. With some notions of Newtonian gravity, we know that measuring gravitational field at $r > R$ for this mass distribution should be exactly equivalent to measuring the gravitational field of a mass $m$ concentrated at $r = 0$. This happens because the fields of all the individual masses add up and lead up to being equivalent to a concentrated mass rather than a distribution. This ideology is extremely important in understanding gravitational radiation. As long as the total mass enclosed inside a given shell is the same and has spherical symmetry, the field outside would be the same irrespective of how it's arranged inside. The analogue of this theorem is the Birkhoff theorem in general relativity.

Birkhoff's theorem states that any spherically symmetric solution of the vacuum field equations must be static and asymptotically flat, meaning it should follow the Schwarzschild metric:

$$ds^2 = \left(1 - \frac{2GM}{c^2r}\right)c^2dt^2 + \left(1 - \frac{2GM}{c^2r}\right)^{-1}dr^2 + r^2d\Omega^2$$

The first time I noticed that this metric has no mention of $R_{obj}$ of the object under consideration, I was so surprised. This means no matter what is the difference in the compactness of two objects in consideration, as long as they are the same mass and spherically symmetric, the metric in their exteriors would look exactly the same. This is because the Schwarzschild solution in the exterior of an object is a vacuum solution, leading to the stress-energy tensor being zero identically everywhere outside the object as long as there is no energy outflow. This is very fascinating to me that the spacetime only obeys the value of one dial, the energy content or mass.

Connecting this back to the original discussion about gravitational radiation, Birkhoff theorem and the Newtonian analogue of it can help us gain better intuition. When it comes to radiation, it can be helpful to break the radiation like a Taylor series in decreasing order of contribution from different mass distributions. The monopolar radiation (if it existed), would come from the zeroth moment of a mass distribution, which is just its total mass. An oscillation of this monopole ($l=0$), often termed as the breathing mode is shown in Figure 2. In this mode, the mass remains unchanged and the spherical symmetry of the object is still intact, but it pulsates about a mean radius. Using Birkhoff theorem here, we can understand that even if the mass distribution is changed in the case of a monopolar oscillation, since the total mass remains the same and spherically symmetric, the external metric also stays the same and there are no tides outside the object. Thus, monopolar gravitational radiation does not exist.

Figure 2: Monopole ($\ell = 0$) breathing mode

The terms following the monopole in the multipole expansion can be understood as various degrees of asymmetry which can be added into the system. The next order term is the dipole as shown in Figure 3. The dipole provides one additional trinket of information about the mass distribution under consideration than the monopole distribution; i.e. the mean or the center of mass of the distribution. If the system is oscillating with a dipolar ($l=1$) mode, we get an idea of the movement of the center of mass of the system. We can then change our frame to have the velocity of the center of mass and can always take our observations in a frame where there is no motion of the center of mass. Thus, dipolar gravitational radiation also does not exist.

Figure 3: Dipole ($\ell = 1$) mode

If we add another degree of asymmetry to our system, we can also measure the deviation of the mass distribution from the mean of it, i.e. the quadrupole moment. If the object is now oscillating in the quadrupolar mode ($l=2$) as shown in Figure 4, it is neither spherically symmetric, nor can we pick a frame in which this effect would go away. A time varying quadrupolar moment thus changes the gravitational field outside the object too causing tides. So for quadrupole, hexapole and other higher oscillations, information about the mass distribution inside the objects leaks into the exterior with gravitational waves. As a very contextual example, neutron stars have a lot of deformities on their surface. We can actually aim to characterize this topology of neutron stars using the continuous gravitational waves emitted by them.

Figure 4: Quadrupole ($\ell = 2$) mode

So yeah, it's all very fascinating and exciting. But to conclude, monopolar and dipolar gravitational radiation does not exist. The leading order contribution to the gravitational radiation is from the quadrupolar mode but higher modes also exist. This is also why we need two polarizations for describing the gravitational waves because they are created using an $l=2$ excitation. I love this field man. Cheers.

Code Used to Generate the Modes

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import animation

from scipy.special import sph_harm

l, m = 2, 0

A = 0.3

omega = 2 * np.pi / 5

R0 = 1.0

frames = 20

T_total = 10

theta = np.linspace(0, np.pi, 100)

phi = np.linspace(0, 2 * np.pi, 100)

theta_g, phi_g = np.meshgrid(theta, phi)

Y = np.real(sph_harm(m, l, phi_g, theta_g))

Y /= np.max(np.abs(Y))

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.set_box_aspect([1, 1, 1])

ax.axis('off')

def update(frame):

ax.cla()

t = frame / frames * T_total

R = R0 * (1 + A * Y * np.sin(omega * t))

X = R * np.sin(theta_g) * np.cos(phi_g)

Y_ = R * np.sin(theta_g) * np.sin(phi_g)

Z = R * np.cos(theta_g)

color = (Y + 1) / 2

ax.plot_surface(X, Y_, Z, facecolors=plt.cm.plasma(color),

rstride=1, cstride=1, antialiased=True)

ax.set_xlim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax.set_zlim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax.axis('off')

ax.view_init(elev=20, azim=frame * 3)

return []

anim = animation.FuncAnimation(fig, update, frames=frames, interval=100)

anim.save("./final_breathing_mode_20.gif", writer="pillow", fps=10)